|

De Benito, J. M. 1993.

|

|

A captive breeding center for the Iberian lynx was recently opened in the National Park of Doñana, Spain. It is believed that the center will play an important role in protecting the limited gene pool of the species as well as provide detailed information of the animal's biology. |

|

|

||

|

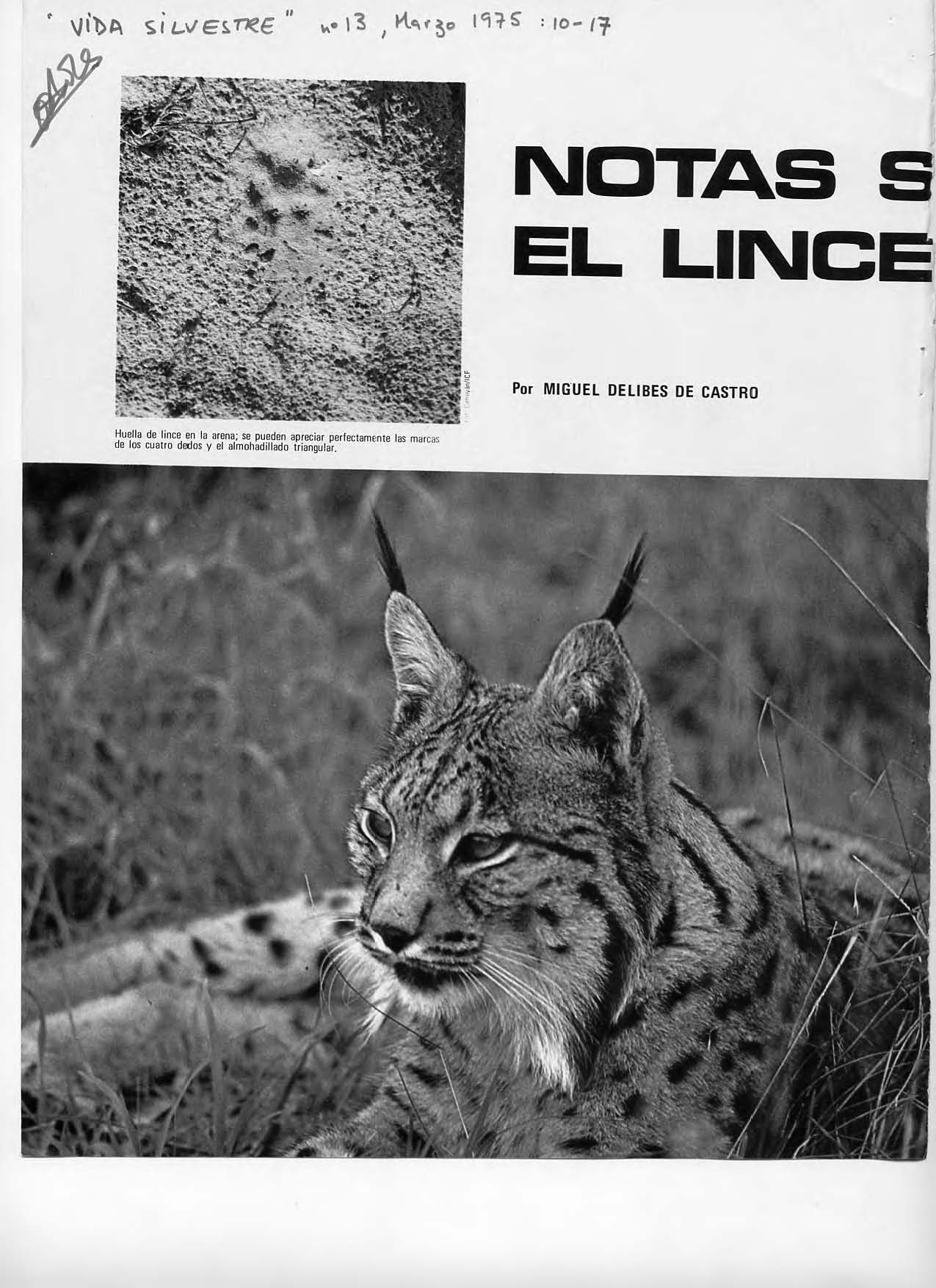

Delibes, M. 1975. |

|

|

|

||

|

© M. Delibes |

|

Delibes, M. 1975. |

|

The aim of this report is to present some examples serving as introduction to the peculiarities in food habits of Mediterranean Iberian predators in relation with their conspecifics in other latitudes, especially temperate Europe. |

|

Delibes, M. 1979. |

|

In the past the lynx inhabited all over Iberia. Today there remain 4 or 5 population concentrations of relative importance (Sierras de Gata and Malca Montes de Toledo, Sierra Morena, Doñana and Sierras in Southern Portugal) and some very small isolated populations. The main reasons for its disappearance are changes in biotopes, direct hunting by man, involuntary and frequent captures by rabbit traps and myxomatosis, which reduced the populations of its mayor prey species. At Doñana the lynx mostly feeds on rabbits (65 to 90% of preys consumed during the year) as well as on Anatidae (especially during the spring and winter) and on Cervidae (especially in autumn and winter). |

|

Delibes, M. 1980. |

|

The present study, carried out in the Reserva Biológica de Doñana (Huelva) from February 1973 to October 1976, endeavours to give information on the following aspects of its biology: - Food: importance of the different preys; seasonal variations; evolution of the trophic diversity, etc. - Factors influencing the diet: prey selection; prey availability, etc. - Influence of predation on prey populations. - Hunting techniques and prey utilisation. - Comparison of the said aspects with the knowledges on other felids, particularly of the genus Lynx. Thus, 1537 droppings, collected in Doñana, were analysed, and several preys, found in the field short time after being killed and/or devoured by the predator, were autopsied. The results of the analysis of faeces have been corrected according to the relation between the number of consumed preys and their frequency of occurrence in the droppings of a captive lynx. |

|

Delibes_1980_El_lince_Iberico_-_Ecologia_y_comportamiento_alimenticios_en_el_Coto_Donana_Huelva.pdf |

|

Delibes, M. 1980. |

|

To study the food habits of the Spanish lynx were analysied 1537 droppings collected throughout two periods of one year in Doñana, S.W. Spain. A food test which was carried out on a captive lynx allowed us to relate the number of occurrences of each kind of prey in the samples with the actual numbers of individual preys and the biomass devoured. The main prey is the rabbit which amounts to 79% of the prey captured and 85% of the biomass consumed. The next in the importance are the ducks (9% and 7% resepectively) and the ungulates (3% and 5%). Seasonal variations in the diet are not very pronounced. The importance of rabbits is at its maximum between July and October, that of the ducks between March and June and that of the cervids between November and February. The prey is selected for the facility in which they may be caught rather than for their abundance. It is estimated that an individual lynx consumes about 74gr of food per kilo of body weight daily. The impact of the predation on the prey populations is difficult to evaluate, but it seems to be very important on the fallow deer population, relatively important on these of rabbits and red deer and very slight on that of ducks. Predation on ungulates in the study area may be a kind of starvation related mortaliy. |

|

Delibes, M. 1989. |

|

The title of my communication can be misleading. Usually, regulation refers to density-dependent mechanisms able to keep a population close to the carrying capacity of the habitat. However, a lot of factors act modifying this carrying capacity in our fast changing developed world. On the other hand, natural population suggests a lack of human influence, something like pre-human conditions of life. But this situation does not occur in Western Europe even in the more protected areas, as it is in the Doñana National Park. Therefore, I will summarize our studies on the factors affecting the size of a non introduced Iberian lynx population in Southwestern Spain. I hope we will be able to obtain some general conclusions, useful for the planning of reintroductions, from this particular case. |

|

Delibes_1989_Factors_regulating_a_natural_population_of_Iberian_lynxes.pdf |

|

Delibes, M. 2002. |

|

The Iberian lynx in one of the species in the Order Carnivora on which more scientific knowledge was accumulated. Thus, it is not possible to plead ignorance to justify its decline, and less still to claim the necessity of more research before adopting measures of conservation. At the same time, we ignore many things that could make more effective these conservation measures. |

|

Delibes, M. 2003. |

|

The author defends the necessity to combine all efforts and avoid the difficulties to save the felid that faces the greatest risk of extinction of the world. |

|

Delibes, M. and Beltran, J. F. 1986.

|

|

The ecology of the guild of carnivores of the Donana National Park has been analysed since October 1982 in order to know their interspecific relationships and to assess the population dynamics and the conservation of the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardina). We have used radio-tracking as a basic field technique, with the following species: lynx (Lynx pardina), fox (Vulpes vulpes), wild cat (Felis silvestris), mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon), badger (Meles meles), and genet (Genetta genetta). This communication summarizes our field experience (research team, traps, radio-tracking equipment and data collection strategies) with special reference to the limitations of the technique and its future use. |

|

Delibes_&_Beltran_1986_Radio-tracking_of_six_carnivores_in_Donana.pdf |

|

Delibes, M., Palacios, F., Garzon, J.,

and Castroviejo, J. 1975. |

|

We have analysed 16 digestive

tracts and 37 scats of Lynx pardina found in Sierra Morena, Montes de

Toledo, Sierra de Gata and Sierra de Lagunilla in Spain, mountains all of them

with an altitude under the 1000-1400 m and a typical mediterranean vegetation.

From 85 preys, even more than the half were Oryctolagus cuniculus

(56.5%). The other preys were rodents (26.9%), birds of the size of the Turdus

and Alectoris (11.7%) and other preys which one of them was a Lacerta

lepida. The rabbits were found in the 86.8% of the contents analysed,

therefore they are the chief food of the Spanish lynx. For this cause the

epidemy of myxomatosis has damaged the last populations of this beautiful cat.

It is even worse for his survival the official authorisations for poisoning and

the systematical destroyment of their biotopes changed with exotic woodland in

great part with Eucalyptus. A pregnant female with three foetuses was

caught the 09-03-1973 in Sierra Morena. The birth would have happened at the

beginning of April and the rutting time must had appeared towards the end of

January and the beginning of February. |

|

Delibes_et_al_1975_Notes_sur_l_alimentation_et_la_biologie_du_lynx_pardelle_en_Espagne.pdf |

|

Delibes, M., Ferreras, P., and Aldama,

J. J. 1993. |

|

Information on: Status of the Doñana lynx population, Factors limiting carrying capacity, Mortality rates and causes, Genetic problems, Other factors, Measures to increase the viability of the population. |

|

Delibes_et_al_1993_Conservation_and_population_dynamics_of_Iberian_lynx.pdf |