Caracal

Caracal caracal

M. Pittet

Description

Molecular evidence supports the classification of the caracal as a monophyletic genus. The caracal is closely related to the African golden cat (Caracal aurata) and the serval (Leptailurus serval). In the past it was classified with Lynx and Felis but is not closely related to them.

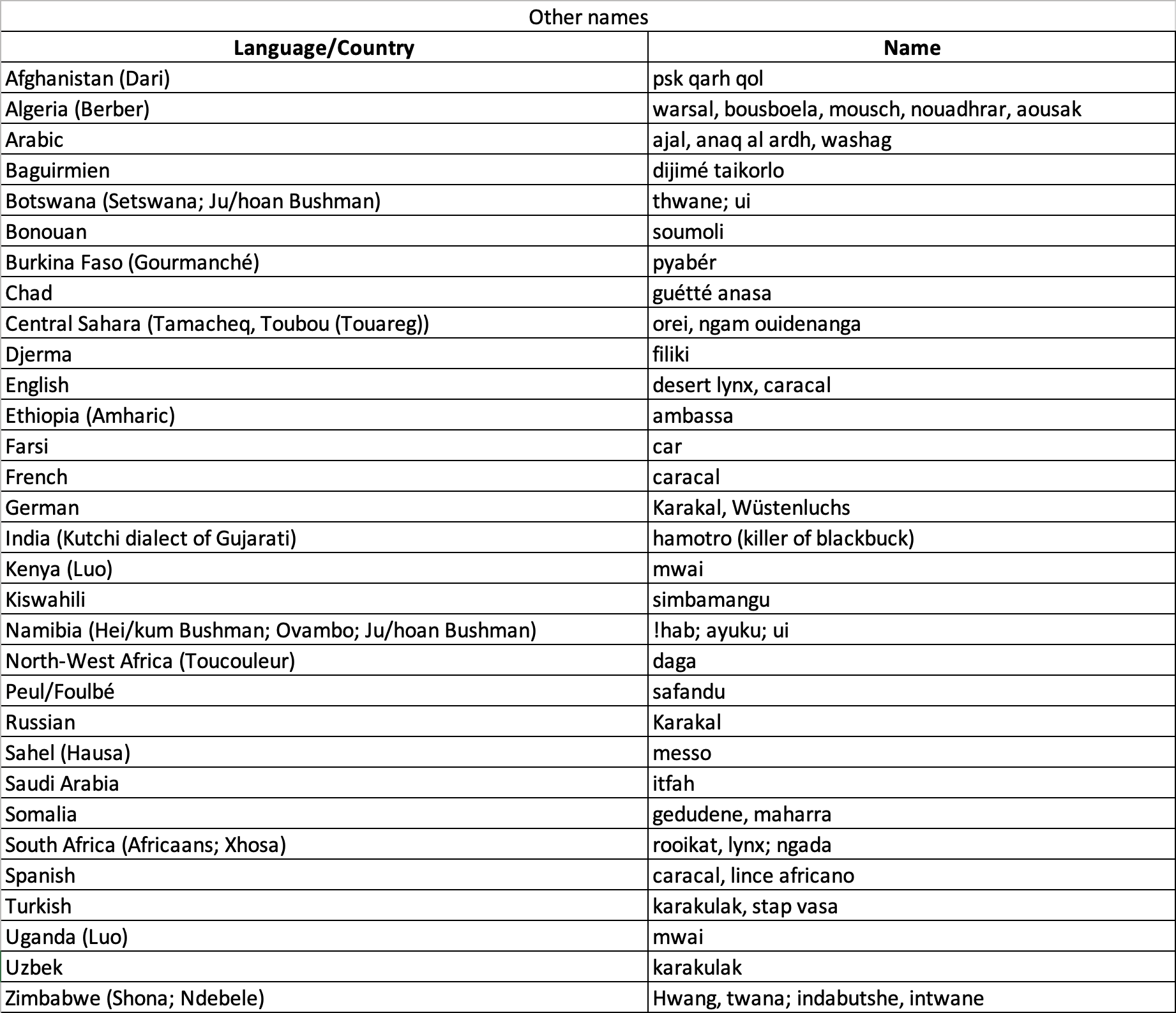

Eight subspecies of the caracal were recognised in the past. However, no recent morphological or molecular studies have been conducted on the caracal. If the phylogeographical patterns found in lions, cheetah and savanna ungulates, also apply to the caracal, it is likely that three subspecies will be distinguished:

-

Caracal caracal caracal in southern and East Africa

-

Caracal caracal nubicus in North and West Africa and

-

Caracal caracal schmitzi in the Middle East to India

Further studies are needed to establish the geographic variation of the caracal.

The caracal is a mid-sized cat with a slender, conspicuous, tall body and long legs. It is the largest of the African small cats. The fur of the caracal is short and tawny-brown to brick-red coloured without any markings, and its underparts are pale. Near the nose and the eyes, the face is marked with dark lines and white spots. Melanistic animals also occur. In central Israel, there was a dark form described with grey adults and black kittens. Its common name comes from the Turkish word karakulak. It means “black ears” relating to its ears which are black on the back and have a triangular shape tipped with 4-5 cm long black hair tufts. Its tail is short and measures about a third of the head and body length. Between its pads, it has stiff hairs as an adaptation to travelling over sand. As with other desert species the caracal has excellent sight and hearing. There is sexual dimorphism with males being on average larger than females in all respects. The caracals in India are somewhat smaller than those of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Weight

6 - 18 kg

Body Length

80 - 100 cm

Tail Length

20 - 34 cm

Longevity

16 - 19 years

Litter Size

1 - 6 kittens

B. Cranke

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) 2016. Caracal caracal. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2024-2

Status and Distribution

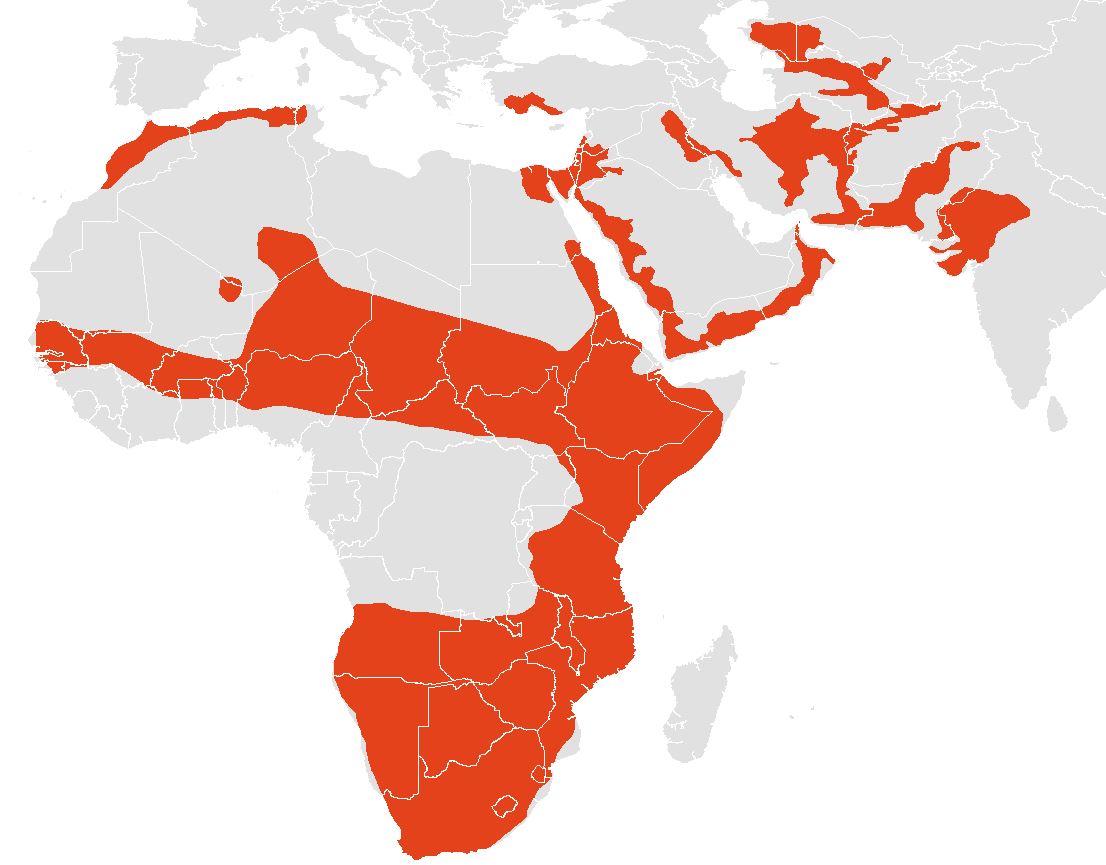

The caracal is listed as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List and in the Red List of South Africa, Swaziland, and Lesotho. In North Africa, it is classified as Threatened, and in Morocco, it is considered Critically Endangered. In Egypt, it is rare. In Israel, it is listed as Vulnerable, and on the Arabian Peninsula, it is listed as Least Concern but may potentially be reclassified as Near Threatened due to declining populations in some range states. It is considered rare in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. In Saudi Arabia, it has been recorded in the southwest mountains and Harrat al Harrah, but its population trend is unknown. In the United Arab Emirates, it is found in wadis in the northern mountains and considered to be declining. In Oman, it has been recorded in various regions, but its population trend and status are not well-known. In Yemen, caracals are thought to be stable and were from the southern and eastern borders. In Hawf Protected Area, Yemen, caracals were considered to be widely distributed and quite common in a study from 2010–2012.

The caracal has a wide geographical range across Africa to central and southwest Asia. It occurs from Africa to Turkey through the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East to Turkmenistan and northwestern India. Within Africa, it is only absent from tropical forests in western and central Africa and the deserts of Namibia and the central Sahara. It is present in the montane massifs and its fringes including Hoggar and Tassili mountains of SE Algeria and the Saharan Atlas, the Aïr of Niger, and edges of the great sand areas of Eastern Great Erg Tun and Alg. Its historical distribution range coincides with one of several small desert gazelles. In 2012 the species was pictured in the Mbari Drainage Basin, Chinko, Central African Republic.

In parts of Africa, it is common and widely distributed, but it has been locally extirpated in areas with high human pressure or extreme habitat change. In North Africa and savannah regions of West and Central Africa, it is rare and patchily distributed. In southern Africa, it is very common and stable, particularly in northern South Africa and southern Namibia. In east Africa, it is common on livestock lands.

In the Central Asian republics and India, the caracal is rare, and its status is not well-known. In India, it is considered locally endangered, and populations are declining. In Pakistan, it is listed as Critically Endangered with an estimated population of 100–150 individuals. In Turkey, it is believed to be very rare and probably endangered, but its status is uncertain. In Iran, it is declining and classified as threatened, except for the Caspian Sea region and the Iranian Caucasus where it is absent. In Afghanistan, caracals were recorded in various provinces, and in Turkmenistan, they were found in the Badhyz State nature reserve. In Uzbekistan, they mainly inhabit the Kyzylkum Desert and the Ustyurt Plateau.

Population trends and estimates for caracals in Asia are largely unknown. In South Africa, a density of 23-47 individuals per 100 km² has been recorded, and in the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve in India, a density of 4.8 caracals per 100 km² were estimated.

Habitat

The caracal is a highly adaptable species that can be found in a wide range of habitats. It is known to inhabit semi-deserts, steppes, savannahs, scrubland, dry forests, moist woodlands, and evergreen forests. It prefers open terrain and drier, arid habitats with vegetation cover. In Turkey, the caracal is often found in maquis vegetation, which is populated with birds and small mammals. On the Arabian Peninsula, it can be found in desert wadis, foothills, mountains, and basalt fields. In Dhofar and eastern Yemen, it has been observed in wooded mountains. In India, the caracal typically inhabits tropical dry deciduous and tropical thorn and shrub forests. A study from the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan, India, showed that caracal occurrence is correlated with the presence of forests and rugged terrain, as these provide cover for hunting, shelter, and prey species. In Iran, caracals are often observed in desert mountains and hilly terrains, which are known to be inhabited by rodents and hares. In Saudi Arabia, a radio-collared caracal showed a preference for well-vegetated wadis with high small mammal densities. At the edge of its distribution range, the caracal can also be found in evergreen forests and mountainous areas in the Sahara. However, it does not inhabit true desert regions or tropical rainforests. In Ethiopia, the caracal has been recorded at altitudes of up to 2,500 m and, in rare cases, up to 3,300 m.

M. Pittet

Ecology and Behaviour

The caracal is solitary and is predominantly nocturnal, but it can also be active during the day depending on its habitat (particularly in protected areas) and the daily temperatures. In the Hawf Protected Area in Yemen for example caracals were mainly active at daytime. The species increases its daytime activity in winters. Usually, the caracal rests in dense vegetation or rocky crevices, and may also use a burrow for shelter during warm days.

The caracal primarily hunts on the ground in spite of being an adept climber although it sometimes uses trees to cache larger kills. The caracal is known for its extraordinary jumping - it can jump two meters or more into the air. It often stalks birds and is then able to spring up and grab them when they take-off. Traditionally, people in India and Iran tamed and used them for sport to watch contests with fenced caracals taking pigeons in this way. The caracal is adapted to dry habitats and is able to satisfy its moisture requirements from its prey when necessary. Nevertheless, watering places are an important feature for caracals, for example in Iran's Kavir National Park, as they can often find prey close by. The caracal is sometimes killed by other carnivores such as lions, hyenas and leopards when ranges overlap. Black-backed jackals can directly compete with caracals, with the two species limiting each other’s distributions.

The home ranges of male caracals are larger than those of the females and typically include several female ranges. Home ranges in arid areas are larger than in more moist habitats. In the Namibian ranch land, the home range of three males averaged 316.4 km². In South Africa, males in the Cape Province had a home range of 31–65 km² and females of 4–31 km². In Israel's Negev Desert, home ranges averaged 221 + 132 km² for males and 57 + 55 km² for females. In Saudi Arabia, one male had a home range of 270-1,116 km² in different seasons. Home ranges are marked with urine, faeces and claw marks. For communication the caracals are also known to actively use their ears.

The reproductive season probably takes place all year round, but in the Sahara, breeding is reported to occur primarily in mid-winter. Females copulate with several males in a “pecking order” which is related to the age and size of the male. Oestrus lasts for 5-6 days, the oestrus cycle for 14 days and the gestation for 78–80 days. The first reproduction takes place at 12.5–15 months for males and at 14–16 months for females. Gametogenesis can occur earlier. One female gave birth at 18 years and caracals have one litter annually. Age at independence is with 9–10 months.

M. Pittet

Prey

The caracal is a generalist predator and occupies a broad unspecialised niche which spans the small-large felid range. Its diet varies from region to region depending on prey availability and abundance. It preys mainly on a variety of small to medium sized mammals and birds. The caracal usually takes prey weighing less than 5 kg such as young antelopes, hares, rodents, hyraxes, birds, mice, invertebrates, fish and reptiles. The caracal also has the ability to take snakes and is known to also kill and eat other small to medium-sized carnivores including black-backed jackals and aardwolfs. The caracal is able to kill prey measuring 2–3 times its own size such as adult springboks or young kudus and goitered gazelles (Gazella subgutturosa). The caracal also preys on domestic animals such as sheep, goats and poultry in some regions. In South Africa, it is also reported to prey on farmed game animals, especially on juveniles. Outside protected areas, domestic stock can make up a significant part of the diet. The caracal often scavenges. In Turkmenistan, tolai hares were the most important prey species. In Algeria, caracals to the northwest of Lake Chad are reputed to hunt dorcas gazelle, hence the local Toubou name is “gazelle cat”. In Iran, rodents seem to play an important part in the diet of the caracal together with ground living birds. In the Bahram’gur protected area, Iran, the main prey species were cape hare and various rodents including Libyan jird. In Israel, caracals prey mainly on hares and birds such as chukars (Alectoris chukar) and desert partridges (Ammoperdix heyi). Sometimes, they also take desert hedgehog (Paraechinus aethiopicus), Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon) and rodents like the Palestine mole rat (Spalax leucodon ehrenbergi) or reptiles. In India, the prey differs from small antelopes such as Chinkara antelopes (Gazella bennettii), weighing some 20–30 kg, and Black buck antelopes (Antilope cervicapra) 25–35 kg and goats to three striped palm squirrels (Funambulus palmarum), Indian hares (Lepus nigricollis), rodents, reptiles such as monitor lizards (Varanus bengalensis), birds, beetles and crickets. In the Arabian Peninsula, caracals feed on birds small mammals, gazelles, lizards and snakes. It takes rodents such as the Libyan Jird (Meriones libycus) but has also been recorded to feed on Arabian sand gazelle (Gazella subgutterosa marica) and once on a steppe eagle (Aquila niplaensis).

Main Threats

Habitat destruction is a significant threat to the caracal, particularly in areas where the species is sparsely distributed, such as in Central, West, North, and Northeast Africa. The caracal is also threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation in the Asian part of its distribution range, particularly on the Arabian Peninsula due to road and settlement construction. Road accidents and the pressure from agriculture and livestock grazing in protected areas within Asia are additional concerns.

Persecution through hunting, trapping, and poisoning is another major threat to the caracal. The caracal is often considered a pest due to occasional livestock predation in semi-arid regions of southern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and parts of Turkey. This often leads to killings due to suspected livestock predation in Namibia, and South Africa. Control measures were employed in the Karoo region of South Africa, resulting in the killing of 2,219 caracals per year from 1931-1952. In Namibia a total of 2,800 individuals were killed. The caracal is also targeted for trophies in South Africa. Additionally, unintentional poisoning can occur through the use of rodenticides.

Livestock depredation by caracals depends on the availability of wild prey and husbandry techniques. When wild prey is scarce, the caracal may take more livestock, occasionally resulting in the killing of multiple animals and escalating conflicts with humans. The caracal is heavily hunted for skins and bushmeat in West and Central Africa. Opportunistic hunting generally is widespread and recreational hunting with dogs and spotlighting is common in some parts of southern Africa. The impact of this hunting on populations, however, is unknown. The caracal seems to be able to withstand a certain hunting pressure but in areas where it is naturally sparsely distributed or where it has been reduced to fragmented pockets hunting is likely to be a significant threat.

The Red List of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho reports an existing international trade in exotic pets. The trade of caracals as exotic pets is a concern, particularly in the USA, Russia, Canada, and the Netherlands, where they are openly advertised on the internet. Although exported cats usually come from legal breeding centers, indications suggest that this trade is growing. The capture of wild caracals is currently regarded as a minor threat in South Africa, but the situation is monitored. The illegal trade of wildlife from Africa to the Arabian Peninsula mainly involves cheetahs. However, it is estimated that some 50–100 caracals are trafficked every year from Somaliland to the Gulf countries. In some markets in the United Arab Emirates caracals have been seen for sale for the international pet trade. The impact of this trade on wild caracal populations is not yet understood.

Prey base depletion, including declines in gazelle populations and reduced rodent prey during droughts, is a serious problem in the Middle East. Domestic dogs are also considered competitors to the caracal. In some regions, such as northern Africa and Asia, there is limited knowledge about the caracal's status and ecology, and little research has been conducted on its spatial and conservation ecology.

In Iran, road kills, retaliatory killings, and attacks by dogs are major problems. In Uzbekistan, the caracal is not recognised as a nationally protected species, leading to cases of retaliatory killing, poaching, and incidental killing. In Afghanistan, habitat loss and hunting pressure are concerns, while in Pakistan, habitat fragmentation, prey depletion, and persecution pose threats. In India, habitat destruction and increased human disturbance are the main challenges for the caracal.

Conservation Efforts and Protection Status

The caracal populations on the African continent are included into Appendix II of CITES, while the ones in Asia are included in Appendix I. The species is legally protected in all range countries on the Arabian Peninsula. However, the caracal is not legally protected in most of its range. Hunting is prohibited in Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mauritania, Mozambique, Nigeria, Zaire, Afghanistan, Algeria, India, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Hunting and trade are regulated in Botswana, Central African Republic, Senegal, Somalia, Tanzania and Zambia. There is no legal protection in Congo, Egypt, Gabon, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Ivory Coast, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Togo, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Oman, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. In Namibia and South Africa, it has the legal status of a problem animal which allows farmers to kill it with varying levels of restrictions. There is no information available for Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Qatar and Western Sahara. Generally, very little is known about the caracal's ecology, behaviour, threats, distribution and status in Asia. There is an urgent need for more research on this species to define its status and effective conservation measures.

There are efforts to improve the knowledge about the status and the ecology of the caracal outside Africa and protected areas. For example, a caracal project to research habitat ecology of the species was established in Turkey. Such projects are important to set priorities and are fundamental for the conservation of the caracal and the development of effective and ecologically sound methods for its management, especially on private land.

Caracals have an adaptive nature which enables them to recolonise vacant areas after local extirpation. Without heavy persecution, the caracal adjusts well to living in human dominated areas. In this regard there is a need to minimise conflict with humans mainly with farmers, and improve small stock protection. Caracals can even be beneficial for crop farmers since they can effectively limit pests such as hyrax populations.