European Wild Cat

Felis silvestris

L. Begert

Description

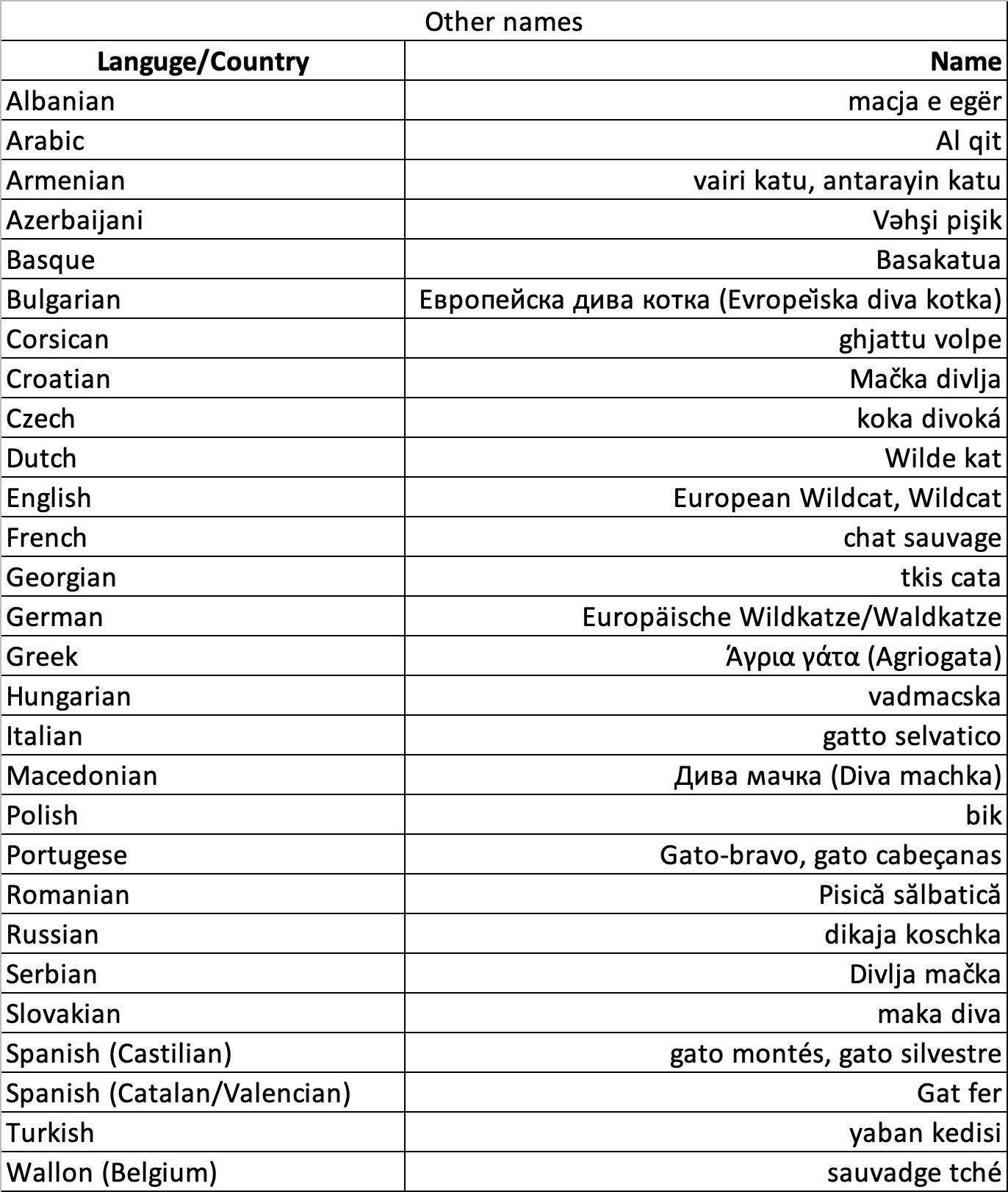

The revised taxonomy of the Felidae recognises the following species of the Genus Felis: Felis chaus (jungle cat), Felis nigripes (black-footed cat), Felis margarita (sand cat), Felis bieti (Chinese mountain cat), Felis silvestris (European wildcat), Felis lybica (Afro-Asiatic wildcat) and Felis catus (domestic cat). The European wildcat (Felis silvestris) includes only the forest cats of Europe. Despite limited information on morphological and genetical differences available, two subspecies of the European wildcat are proposed based on current geographical isolation:

-

Felis silvestris silvestris in Europe, including Scotland, Sicily and Crete and

-

Felis silvestris caucasica in the Caucasus and Anatolia, Turkey.

Fossil records indicate that the European wildcat is the oldest form descended from Martelli’s cat (Felis silvestris lunensis) about 250,000 years ago. The only ancestor of the domestic cat is the Afro-Asiatic wildcat Felis lybica. Hybridisation is common between European wildcats and domestic cats. Hybridisation between European and Afro-Asiatic wildcats can occur when ranges overlap as well, e.g. in a possible contact zone in the southern Caucasus and in eastern and southern Anatolia.

The European wildcat is the size of a large domestic cat. It has a broad head and wide set ears. The coat of the European wildcat is thick and long (during the wintertime), grey-brown with a well-defined, individual pattern of black stripes on the head, neck, limbs, and has a distinct dorsal line. The European wildcat has a bushy, blunt-ending tail with several black rings and a black tip. Some individuals have a white spot on the throat. In its winter coat, the European wildcat looks rather compact and short-legged, although this cat actually has longer legs than most domestic cats. Melanistic individuals have never been recorded in Europe.

Weight

3 - 8 kg

Body Length

45 - 80 cm

Tail Length

ca. 30 cm

Longevity

10 years in the wild, 12 - 16 years in captivity

Litter Size

1 - 8 kittens

L. Geslin

Status and Distribution

The European wildcat (Felis silvestris) is a widespread species and listed as Least Concern in the IUCN Red List. However, over large parts of its range, reliable information on its conservation status is lacking and thus its range-wide population trend unknown. The European wildcat is considered threatened at the national level in many range states. In the respective National Red Lists, it is listed as Least Concern in France, as Near Threatened in Spain, as Endangered in Albania, Bulgaria and Poland, and as Critically Endangered in Scotland.

The European wildcat inhabits parts of Europe and parts of adjoining Russia into central Asia. Formerly the European wildcat was widely distributed in Europe and only absent from Fennoscandia. Between late 1700 to mid-1900, European wildcat populations declined considerably and locally the species was extirpated. In the Netherlands, Austria, and probably in the Czech Republic, it disappeared completely. Several countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Scotland, Slovakia and Switzerland) were re-colonized by the European wildcat between 1920 and 1940. Recently, there has been evidence of wildcat presence in some regions of Austria, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands. In the United Kingdom, the wildcat was nearly extinct by the time of the First World War. The small population that had survived in the northwest of Scotland re-colonized most of Scotland, but not England before declining again. Today, the Scottish population is no longer deemed viable and considered to be virtually extinct. The only Mediterranean island populations of European wildcats are found on Sicily and Crete. Their status on Crete is uncertain and they are assumed to have been introduced to the island. Its distribution range can be split into five continental metapopulations:

-

The Western-Central Europe metapopulation ranges over central and north-eastern France, south-western and central Germany and includes Luxembourg, Wallonia in Belgium, Province of Limburg in the Netherlands and the Swiss Jura extending onto the Swiss Plateau and probably the (Pre-) Alps.

-

The Apennine Peninsula and Sicily metapopulation is expanding its distribution and thought to be increasing.

-

The Eastern-Central, Eastern and Southeastern European metapopulation ranges over 20 countries. The wildcat is relatively widespread but, in most countries, a neglected species and possibly more fragmented than currently assumed. Its trend is unknown.

-

The metapopulation on the Iberian Peninsula is declining, highly fragmented and split into possibly isolated populations.

-

The metapopulation in Turkey and the Caucasus, where the wildcat is common in the European part of Turkey in the north and eastern part of Thrace, in parts of Edirne, Tekirdağ and Istanbul. The subspecies F. s. caucasica is found in Anatolia in Turkey and the Caucasus Mountains in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Russia. The status of this subspecies is unclear and hybridization with F. lybica might occur.

Generally, in some parts of the European wildcat distribution range, probably only few genetically pure individuals remain due to hybridisation with domestic cats. In Scotland, it is estimated that over 80% of cats found in the wild may be hybrids or feral cats. In Hungary and Italy, the proportion of hybrids is estimated to be 25-31% and 8% respectively. In Germany, 3.9% of cats were identified as hybrids. Hybrids have also been detected in Belgium, Portugal and Switzerland. In other European populations, the proportion of hybrids among pure wildcats varied from 3-21 %. Populations of European wildcats in Eastern Europe are generally considered to be genetically relatively pure. In several range countries, changes and trends in population size and distribution are not well documented and only rough estimates exist. European wildcat populations are often fragmented and decreasing, e.g. on the Iberian Peninsula. However, in Germany and France, populations have been expanding in the last years and previously isolated subpopulations are increasingly merging. Estimated densities of the European wildcat vary highly between 0.7 to up to 250 individuals per 100 km².

Using a low average density of 10 wildcats per 100 km2 and considering only the extant area of the species, results in a rough global population estimate of 140,000 European wildcats. Trend information exists only for few countries or for separate populations.

M. Pittet

Prey

The staple diet of the European wildcat are rodents such as rats, mice and predominantly voles. In areas where rabbits occur such as central Spain or parts of Scotland, they tend to be the preferred prey of the European wildcat. The European wildcat occasionally preys on insectivores, birds, insects, frogs, lizards, hares and poultry or even smaller carnivores such as martens, weasels and polecats. They have also been found to be possible predators of European pond turtles in Slovakia. European wildcats also scavenge and cache food. The diet of the European wildcat shows only minor seasonal variations with rodents or rabbits as the major prey item throughout the year.

Ecology and Behaviour

European wildcats are considered solitary, mostly nocturnal and territorial predators. In areas with little human activity, wildcats are often active also during the day, with activity peaks at dawn and dusk. In western Scotland, it was found that European wildcats can travel over 10 km per night to forage on open ground and rested in thickets or young forestry plantations during the day. Shelters near forest edges are preferred for resting sites. European wildcats often use burrows of other mammals, such as foxes or badgers, as den sites.

Home range sizes can vary considerably. For example, in Cabañeros National Park, Spain, home range sizes were found of up to 60 km², whilst home range sizes in Hungary differed between 1.5-8.7 km². Home range size can vary dependent on different factors including prey availability, sex and seasonality. For example, in Scotland it was found that in areas with an abundance of rabbits, home range sizes can range from less than 1 km² to about 6 km². Whilst in Scottish areas where wildcats mainly rely on smaller prey like mice and voles, home range size was estimated at 8-18 km². Additionally, males tend to have larger home ranges than females and usually male home ranges overlap with the ranges of 3-5 females. Home range overlap between individuals of the same sex, however, is low. For example, in an agricultural area in Germany, average home range sizes were 11.9 km² and 2.9 km² for males and females respectively. Similarly, in Maremma Regional Park and Paradiso di Pianciano Estate in central Italy, average male and female home ranges were estimated at 22.8 km² and 6.5 km² respectively. Home ranges too can vary based on seasonality. Males enlarge their home ranges during the mating season in the late winter and early spring, e.g. a male in Scotland enlarged its home range from 5 km² to 25 km² during that time. Females, on the other hand, enlarge their home ranges during summertime, when they are rearing their offspring.

European wildcats are influenced by competition and avoidance of larger predators, such as the Caracal Caracal caracal and Caucasian lynx Lynx lynx dinniki, the red fox Vulpes vulpes and golden jackal Canis aureus. Generally, European wildcats only live in sympatry with larger felid species in habitats where they can take refuge from them. In Spain and France, wildcats have been found to spatially avoid red foxes and to be negatively affected by the recovery of the red fox population. Additionally, higher cortisol levels were found in European wildcats exposed to golden jackals, which possibly is a result from the interspecies competition for territory and food.

Not much is known about the social behaviour of the wildcat. There is evidence that individuals are in contact either by olfactory or vocal communication with at least their neighbours. The European wildcat uses scent marks (urine spraying in both sexes and uncovered faeces) for communication. Vocal communication occurs throughout the year, but most frequently in the mating season. The wildcat almost exclusively hunts on the ground, although it is an excellent climber, and usually stalks its prey followed by a quick attack.

The mating season is in late winter, namely between January- March. Most births take place in April and May. Females can only breed twice in one year under exceptional circumstances such as when the first litter is lost. The oestrus cycle lasts for 1-6 days when males are present and the gestation for 64-71 days, on average 68 days. Age at independence can vary from 5-10 months and sexual maturity is reached by females at 6.5-11 months and by males at 9-10 months. Kittens start to eat solid food when they are one month old, are weaned at the age of 3.5–4.5 months, and learn to hunt progressively between 3-5 months of age.

Main Threats

One of the main threats to the European wildcat is hybridisation with domestic cats which can lead to the loss of genetic variation or to the loss of specific adaptations. Such hybrids are found almost throughout its entire range and there may be very few genetically pure European wildcat populations remaining. The impact of hybridisation, however, is still not known. Hybrids between wildcats and domestic cats can look very similar to the wildcat which makes it difficult to assess the status of the European wildcat.

Other potential threats to European wildcats include the disease transmission from domestic cats (such as Feline Immunodeficiency Virus and Feline Leukemia Virus) and competition with feral cats for food. Additionally, wildcats can be threatened by human-caused mortality. Many wildcats get killed on roads or as by-catch in control measures for other carnivores. Rodenticides may also threaten wildcat populations, e.g. 27% of collected cat carcasses collected from roads in Scotland had rodenticide concentrations at levels that would cause mortality in other species. Illegal persecution through predator control activities still occur in Iberia and in Scotland, the level of persecution, however, is not known.

In the 18th and through the mid-20th centuries habitat loss and fragmentation as well as direct persecution have led to sharp declines of European wildcats in Europe and Russia. In Albania wildcats are still poached or captured alive and kept in captivity as pets. Although the European wildcat can adapt to cultivated landscapes to a limited degree, habitat loss and fragmentation can still pose a problem. In some areas prey reductions further threaten the wildcat. The risk of hybridisation with domestic cats is increased in cultivated landscapes.

The impact of climate change on wildcats is unknown and may be different in various parts of the species’ range. Generally, little robust information is available on the effect and severity of many threats like hunting, forestry and agriculture, habitat loss, decrease in ecological connectivity and habitat isolation, therefore further studies are needed.

Conservation Efforts and Protection Status

The European wildcat is included in CITES Appendix II, listed in the EU Habitats and Species Directive Annex IV, and the Bern Convention Appendix II. It is fully protected over most of its range under national legislation. Hunting is prohibited in Armenia, Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Moldavia, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and Ukraine and regulated in Azerbaijan, Romania and Slovakia. It has no legal protection outside reserve areas in Bulgaria, Georgia and Romania. No information is available for Albania, Croatia and Slovenia.

The inclusion of the European wildcat into the Bern Convention and the European Habitat Directives has helped the species to recover in some parts of Europe after having sharply declined in many areas and been extirpated in others. The European wildcat re-colonized many countries between 1930 and 1940.

The most urgent conservation need is to identify genetically pure wildcats and to prevent hybridisation. However, this task is difficult as wildcats cannot easily be distinguished from domestic cats or hybrids. Further research on hybridisation levels may warrant a reassessment of the wildcat as a threatened species due to population declines of genetically pure wildcats. In Europe, progress has been made towards defining the felid “units of conservation”, combining studies of morphology and genetics to clarify the relationship between wildcats and domestic cats. Established morphological criteria and genetic markers should help to more easily distinguish hybrids from pure wildcats.

In most range countries research and conservation efforts at the population level is lacking and no specific conservation actions are in place. Additionally, there is a need for research at the metapopulation level. For the European wildcat, reliable information is only available on population dynamics and change of the distribution range at local or national scale, but there is no consistent transboundary compilation of scientifically robust information at a metapopulation level. Focus on wildcat conservation has been mostly local, with populations or metapopulations receiving uneven attention. In the case of Scotland, this reflects the critical status of the population, but otherwise is unrelated to the range expansion or assumed conservation status of the population. A review of the conservation status of the Scottish wildcat deemed the remaining population as inviable. The review recommended the strengthening of the remaining population with captive breeding and/or translocation from the genetically closest continental population.

Further research is needed in regard to the impact of threats to define further conservation actions. The development of a conservation strategy for the European Wildcat is suggested to help propagate, coordinate and implement conservation efforts for the species and thereby provide a strategic guideline for the development of national and international wildcat projects.

Habitat

The European wildcat is primarily associated with forest habitat and most abundant in broad-leaved or mixed forests. They show a preference for structurally rich forests. However, it also inhabits grassland and steppe habitats and can be found in coniferous forests, the Mediterranean maquis scrubland, riparian forest, oak forests, marsh boundaries and along sea coasts or in very wet, swampy areas. Contrary to previous beliefs, recent studies found that European wildcats can also regularly use agricultural landscapes, as long as there are sufficiently large (> 100 ha) forested areas within 6 km distance. Agricultural areas are usually rich in rodents and/or lagomorphs, i.e. wildcat prey. They can also inhabit fragmented landscapes with a mixture of forests, agricultural fields and grasslands. Females seem to be more forest dependent than males, probably requiring sheltered areas for the rearing of offspring. Even relatively large rivers do not necessarily present barriers to wildcats, as they have been observed crossing the Rhine in places without bridges or other crossing structures. In the Pyrenees, European wildcats are found up to 2,250 m elevation and also occur in the Swiss Jura mountains.

_JPG.jpg)