Kodkod

Leopardus guina

A. Sliwa

Description

The guiña (or huiña) is the smallest felid in the American continent and one of the smallest in the world (1.5-3.0 kg).

From an evolutionary perspective, guiñas are closely related to six other small Neotropical cats of the genus Leopardus belonging to the Ocelot Lineage. This exclusive Neotropical lineage diverged from a common ancestor around the formation of the Panamanian land bridge 2.8 million years ago (Ma). The guiña's sister species, the Geoffroy’s cat (Leopardus geoffroyi), which last shared a common ancestor less than 1 Ma, is found along the eastern side of the Andes mountain range. Two subspecies of the guiña are recognised based on morphological and genetic data:

-

Leopardus guigna tigrillo in North and Central Chile (30° to 39° S) which has a lighter coat and larger body size and

-

Leopardus guigna guigna in South Chile (38° to 48°S) and South-West Argentina (39° to 46° S) which is darker and smaller.

Based on the two subspecies, two main management units were identified for the conservation of the guiña.

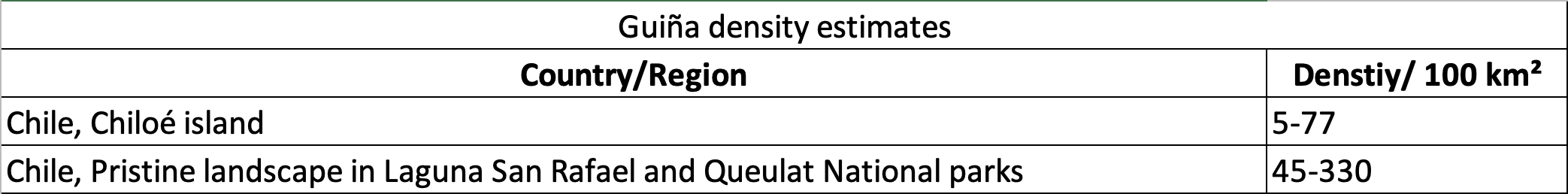

The guiña looks similar to its close relative the Geoffroy’s cat, but the Guiña has a smaller face with distinctive markings, a thicker, bushier tail and is slightly smaller. The coat of the guiña is buff, grey-brown or reddish brown with many small black spots and its lighter belly is spotted too. The face of the guiña is characteristically marked: from each eye a black line crosses the cheek under the eye and another solid black stripe rises vertically on either side of the nose to the crown. Its ears are relatively small, rounded and have a black backside with a white central spot. Some individuals have prominent dark stripes across the throat. The guiña’s tail is black ringed and is about half of the head body length. Male guiñas are larger than females. Melanism is quite common in some regions. On Chiloé island and the Guaitecas islands in the Araucanía Region, the Queulat and Laguna San Rafael National Parks, and in the Neuquén Province in Argentina melanism seems to be particularly common but within the geographic range of the northern subspecies melanism is not known to occur.

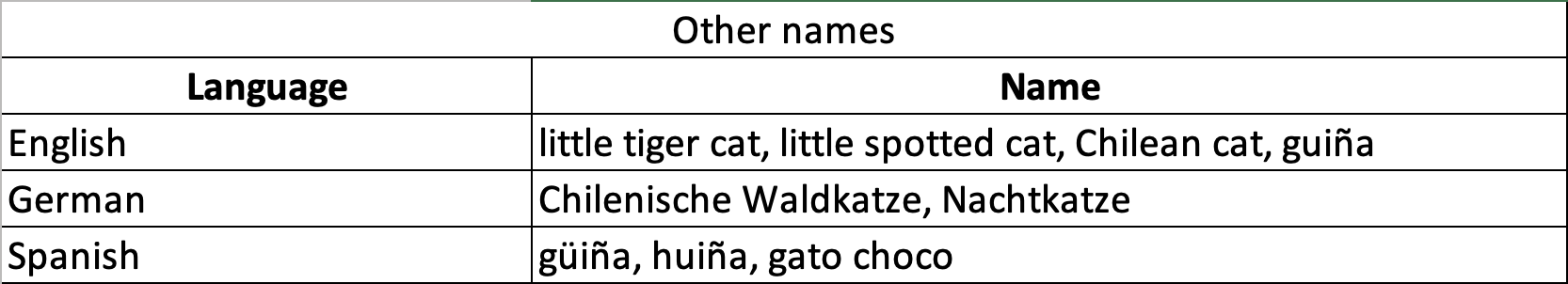

The guiña is sometimes also called kodkod. However, this name is not used in many range countries and its origin is not clear. The name may also possibly refer to the pampas cat and not to the guiña.

Weight

1.5 - 3 kg

Body Length

37 - 56 cm

Tail Length

20 - 25 cm

Longevity

up to 11 years

Litter Size

1 - 4 cubs

P. Meier

Napolitano C, Galvez N, Bennett M, Acosta-Jamett G & Sanderson J. 2015. Leopardus guigna. 2015. Leopardus guigna. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2024-2

Status and Distribution

The guiña along with the Andean cat (Leopardus jacobita) is the most threatened cat species in South America, and the only carnivore endemic to the Patagonian Andean forests. The guiña is classified as Vulnerable in the IUCN Red List and in Argentina, while in Chile it is considered Vulnerable from Los Ríos Region to the north and Near Threatened from Los Lagos Region to the south. In Argentina, the National Parks Administration considers this species of “special value”, and it is included among the high-priority species to conserve. Because of the little attention received and its high vulnerability, the guiña was highlighted as a main research priority in Argentina, but in spite of this priority, few studies have been conducted and a lot of information about this forest cat remains uncertain.

Using a theoretical metapopulation approach it was estimated that the guiña population is divided into 24 subpopulations in central Chile.

The guiñas northern range in central Chile is inhabited by more than half of the country's total human population which dramatically reduces the available habitat. In its southern range, its status seems to be more stable since human density is lower and more protected areas are in place. In Argentina, the guiña inhabits exclusively the Patagonian National Parks' jurisdiction, and its populations occur in low densities and are probably suffering local extinction processes but the factors and threats involved are still ignored.

The guiña has the smallest range of any new world felid inhabiting around 160,000 km². It occurs only in central and southern Chile (30°-48° S) and in a narrow strip of south-western Argentina (39°-46° S west of 70°W), including some offshore islands such as Isla Grande de Chiloé. The guiña is found up to an elevation of 2,500 m and is sympatric with the Geoffroy’s cat only in the eastern limits of its range in Argentina. In Argentina, the guiña is also sympatric with the Puma (Puma concolor) in forest ecosystems.

Habitat

Vegetation cover is an important ecological requirement for the guiña as it typically occurs in forest with heavy understory. In its southern range, it is strongly associated with moist temperate mixed forests of the southern Andean and Coastal ranges, particularly the Valdivian and Araucania forests of Chile. A characteristic of these forests is the occurrence of southern beech (Nothofagus spp.) and bamboo in the understory. In south-west Argentina it is found in the Andean Patagonian Forest. In its northern range, it inhabits Mediterranean matorral and is found more in sclerophic forest and thicket. In Argentina guiñas have also been recorded within Subantarctic forests and Valdivian-like montane forest with bamboo structures, lianas and epiphytes. Radio-collared individuals were also observed to make particular use of forest edges. Forest patches that were smaller than 0.5 km² were used relatively rarely.

Guiñas seem to be relatively tolerant of altered habitat and are also recorded in secondary forest, pine or eucalyptus plantations, semi-open habitats or close to agricultural areas. Nevertheless, guiñas are not observed using or crossing grazed pasture with vegetation <0.4 m high. Guiñas were observed crossing open habitat only up to distances of 100 m to reach suitable habitat patches again. Thus, it is assumed that vegetated corridors are important to connect habitat patches.

P. Meier

Ecology and Behaviour

Activity patterns of the guiña possibly vary in different regions and are potentially influenced by coat coloration. It can be active at day and night. Melanistic individuals showed stricter nocturnal activity than spotted ones. The guiña is a good climber, escaping to trees when threatened and it likes to shelter in trees during inactive periods. Guiñas also rest in dense cover near waterways and in thick piles of ground-level vegetation or quila thickets. Daily distances covered by radio-tracked guiña were up to 1.8 km in Torres del Paine and Queulat National Parks, and a maximum of 13.9 km in a fragmented landscape on the northeastern coast of Chiloé Island, revealing its high and facultative dispersal ability. Guiñas are agile hunters and mainly hunt on the ground.

Home range size of guiñas is 0.3-2.2 km² in Torres del Paine and Queulat National Parks, and 1.3-22.4 km² in a fragmented landscape on the northeastern coast of Chiloé Island. Average home range size in the Chilean Araucanía region was 6.23 km². The ranges of males are often larger than those of females. Male and female home ranges overlap largely whereas home ranges of individuals of the same sex are exclusive. However, a radio-collar study in 2004 in Chile found spatial overlap both within and between sexes. Gestation period lasts about 72–78 days.

Prey

The guiña in southern Chile preys mainly on small mammals like rodents, marsupials (i.e. Tyhlamys elegans, Dromiciops gliroides) and lagomorphs (i.e. exotic Oryctolagus cuniculus) but also on birds and invertebrates. It is also known to frequently feed on lizards and to occasionally take carrion and predate on poultry as well. In the Malleco National Reserve, Chile, the majority of prey consisted of arboreal/scansorial small mammals, although ground-dwelling ones appeared to occur more frequently in the area. On Chiloé, besides rodents, also austral thrush, lapwings, chucao tapaculo, hued-hued, chickens and a goose were identified as prey. This is also observed in Argentina. Its diet does not seem to change significantly between seasons.

P. Meier

Main Threats

Current threats for the guiña include habitat loss and fragmentation mainly due to logging, agriculture and livestock rearing, habitat conversion to pine plantations and direct persecution by humans. Due to its restricted distribution and ecological requirements, it was believed that the guiña is especially vulnerable to habitat loss and fragmentation. However, a recent study indicated that the guiña might be able to cope better to some fragmentation than previously thought. Logging and deforestation has most probably resulted in population fragmentation in the northern part of its range, while in the southern part these threats are a problem in the remnant temperate Valdivian rainforest.

A study based on climate change models predicted a 52% loss of climatically suitable areas for the guiña by 2050. However, the model was based on a rather small number of known occurrence records (N=15). A second study using 86 records predicted a range loss of 39% by 2050 (minus 58.6% in Argentina, minus 32.5% in Chile) from climate change and change in human land uses.

Since the beginning of the past century, many economically important non-native wild fauna have been introduced to Argentinean Patagonia to generate income. As a result, many native species, including the guiña, are valued less. In some areas the guiña is considered to be harmful vermin due to the predation of domestic poultry. In one study in the Valdivia area and on Chiloé Island, despite 66% of farmers acknowledging that confinement is necessary to protect their animals, up to 54% of farmers left their animals permanently unconfined. At the same time, 48.6% of participating farmers disliked guiñas, 57.5% regarded them as (very) damaging, and 19.8% wished for their population to decrease and 17% for them to disappear altogether. Illegal killing seems to be quite frequent throughout its range. Every year guiñas are killed in retaliation for poultry depredation, and this has happened even within Lanin National Park (Argentina) in recent years. Negative attitudes are often based on popular beliefs, myths and symbolism and not necessarily on the actual amount of damage caused. Some people erroneously consider the guiña as a “vampire” that sucks the blood of their prey without eating them. Guiñas are also killed by dogs, and road kills are a major problem.

A study on Chiloé Island identified positive cases of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) and Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) in guiñas, probably transmitted from co-occurring domestic cats. In Los Ríos region, Chile, free-ranging, unvaccinated domestic cats were found to be abundant, to overlap with guiñas. As such, they pose a risk for pathogen spillover.

Conservation Efforts and Protection Status

The guiña is included in Appendix II of CITES and fully protected in Argentina and Chile.

The preservation of native vegetation corridors is required to provide connectivity between forest fragments or larger forested areas. Human populations and deforestation are increasing in the Chilean temperate rainforest and climate change may be an emerging additional threat. National Parks in Chile are mainly established at higher elevations in the Andes (>800 m) whereas the guiña is also found at lower elevations. Thus, the conservation of guiñas in private lands outside protected areas has particularly important for the long-term persistence of its populations. A change in attitude of landowners towards guiñas is required.

Long-term conservation challenges for the guiña outside protected areas will depend on the increase of local awareness to reduce conflict in areas where they are considered poultry pests, improving chicken coops and highlighting the services provided by its role as controller of mice - carriers of Hanta virus - and exotic European hares (Lepus europaeus).

A future challenge would be to understand and manage the potential pathological effect and emerging disease risk both FIV and FeLV infections may have for guiña populations.

More information about the ecological requirements, demographics, natural history, threats and the status of the guiña is needed, along with continuous population monitoring to enable accurate long-term conservation measures.