Sand Cat

Felis margarita

M. Pittet

Description

The sand cat (Felis margarita) is part of the genus Felis. Previously, four subspecies of the sand cat were described:

-

F. m. harrisoni from the Arabian Peninsula

-

F. m. scheffeli from the Nushki Desert of Pakistan

-

F. m. thinobia from the sand deserts of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and probably northern Iran and north-eastern Afghanistan, and

-

F. m. margarita from North Africa.

Based on the most recent studies, only two subspecies are proposed:

-

Felis margarita margarita in North Africa and

-

Felis margarita thinobia in South-West Asia and on the Arabian Peninsula

Further phylogeographical studies are needed to confirm this classification.

After the black-footed cat (Felis nigripes) the sand cat is the second smallest member of the genus Felis. The coat of the sand cat is strikingly pallid with the typical camouflage of a sand-dwelling species: its back is pale sandy-isabelline, finely speckled with black over the shoulders and with silvery grey on the upper flanks. It has a poorly differentiated spinal band and its crown is a pale sandy colour, marked with ill-defined striations. Some individuals have dark horizontal bars on the legs. The tail of the sand cat is long with 2-8 black rings and a black tip. The belly and throat are white. The face is marked with a dark reddish-fulvous stripe from the anterior edge of each eye backwards, across the cheeks. The hair on its cheeks is white, too. It has large yellow amber, green or yellow-bluish eyes. The sand cat’s ears are very large, black-tipped, set widely apart and low on the sides of the broad and flattened head. The front paw of the sand cat has five digits whereas the hind paw has only four. The claws are not very sharp, except for the dew-claw on the thumb higher up on the wrist, due to the lack of opportunity to sharpen them in the desert and the sand cat's digging habits. The sand cat does not retract its claws completely when walking and impressions of them are sometimes visible in its tracks. Males are on average larger and heavier than females.

The desert-dwelling sand cat must endure extreme temperatures. In the Sahara, summer temperatures may range from 58° C in the shade during the day to -0.5° C at night. In the north of its range, winter temperatures may reach -25° C. Adaptations include dense dark fur growing between the toes and on the soles, completely covering the pads to insulate the paws against the heat and cold. In northern regions of its distribution, the sand cat's winter coat can be very dense and may be up to 6 cm long with soft woolly underfur, making the cat appear much larger. The inside of the ear is covered with thick white hair which probably has a protective function against sand during storms. The tympanic meati (passages from the external ears to the ear drums) and bullae (rounded bony capsules surrounding the middle and internal ears) are greatly enlarged (compared to the ones of other small felids) to increase hearing abilities in areas with little vegetation cover. A highly developed sense of hearing is important for locating sparsely distributed, often fossorial, prey in arid environments.

Weight

1.35 - 3.4 kg

Body Length

39 - 52 cm

Tail Length

22 - 31 cm

Longevity

upto 17 years in captivity

Litter Size

2 - 8 kittens, avg. 3

M. Pittet

Status and Distribution

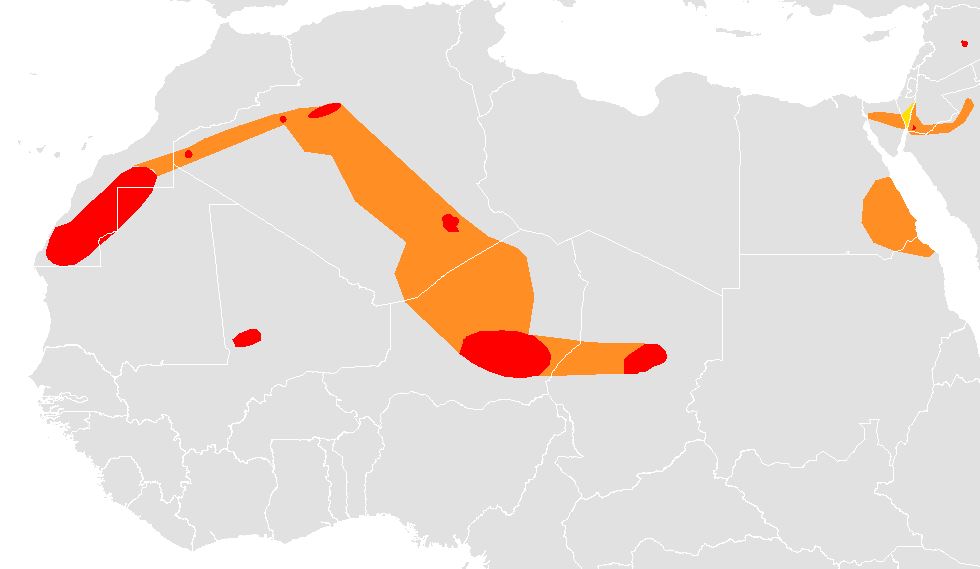

The sand cat is classified as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List. Due to the still limited knowledge about its ecology, distribution and population size, it is difficult to assess the status of the species. Despite the existence of only few records across its range, the patchiness of its distribution and the detection of some local declines, there is not sufficient evidence to assume a range wide decline of the species which would qualify it for a threatened category. However, there are no reliable population estimates or trends available. The species is often described as rare and occurring at low densities. However, its nocturnal and secretive behaviour may influence this perception. In low quality habitat such as areas with shifting sand dunes, densities of sand cats are assumed to be very low. Sand cat numbers probably fluctuate with the peaks and dips in prey densities caused by environmental conditions. In the Regional Red List of the United Arab Emirates, the species is classified as Endangered, and in the Regional List of the Arabian Peninsula as Near Threatened. The national Red List of Israel lists the sand cat as Critically Endangered.

The density of the species was estimated at 2.9 individuals/100 km² in Israel. In Saja/Umm Ar-Rimth Protected Area, Saudi Arabia, the sand cat density was estimated at 16.66 and at 14.27 / 100 km² in 2002 and in 2005, respectively. The total sand cat population is conservatively estimated at 27,264 mature individuals. For the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, less than 250 mature individuals are estimated, and the Arabian sand cat populations are thought to be declining across their range.

The distribution of the sand cat is discontinuous. In northern Africa, the sand cat occurs marginally in the Western Sahara and was recorded in Algeria in and around Ahaggar Cultural Park, the Grand Occidental, the Béni Abbès region and the Tindouf area. The sand cat has also been recorded in Niger in the Termit & Tin-Toumma National Nature Reserve and Chad and sighted in Mali. In Mauritania, it historically occured in the Adrar mountains and Majabat al-Koubra. Its presence in Sudan is uncertain. There are records ranging from the Sinai Peninsula to the rocky deserts of eastern Egypt. There are no confirmed records in Egypt west of the Nile River, in Libya and in Tunisia. There are records from scattered locations across the Arabian Peninsula. The status and distribution of the sand cat is not well known but the population is considered to be declining across the Peninsula. In the United Arab Emirates, the sand cat is rarely recorded. It has been found in Abu Dhabi and Dafar and Umm Al Zuma in the south-east and on the edge of the Rub Al Khali. In Oman, the sand cat has been recorded in the Empty Quarter, in Ramlat al Ghafa, Umm as Samim and south-west of Ibri as well as in the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary in the central region, in the As Saleel Nature Reserve and the Wahiba Sands. There have been no records from Yemen for more than 50 years. In Saudi Arabia, there are repeated reports from the south-west and from the south-east bordering Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Sand cats have been recorded in the protected areas Mahazat as Sayd, Saja/Um Ar-Rimth and Uruq Bani Ma'arid as well as in the western Empty Quarter. The species has also been reported from Qatar and Kuwait. In Jordan, the sand cat is considered very rare. There are some records from Wadi Rum in the south and from the north-east, but extensive trapping failed to record the species in Wasa Arava. In Syria, sand cats were recorded around the area of Palmyra. In Iraq, the sand cat has been recorded in the West Al-Najaf desert area. In Pakistan, sand cats have been recorded in the Chagai Desert plateau of the Balochistan province close to the border with Afghanistan and from the south-east and east, near the Iranian border, however these records are more than 40 years old and there are no recent records form the country. In Iran, sand cats are mainly recorded in the desert habitats in the centre, east and south-east of the country, with some records from the north. The sand cat is known from the Khorasan Province in the north-east, Kavir National Park in the north-centre and Fars Province in the south-west. It has also been camera trapped in the Abbassabad Protected Area, east of Isfahan. The species was detected east of the Caspian Sea in Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. In Uzbekistan, a breeding population of sand cats has been recorded in the Kyzyl Kum desert in 2013/2014. During a survey in 2015 in the Kazakh Kysylkum, sand cats were not detected and from the Karakum desert in Turkmenistan records are missing too.

No ecological explanation exists for the gaps in the sand cat distribution. It is not known if the gaps in its distribution range are due to a lack of surveys or reflect species absence.

P. Meier

Habitat

The sand cat is the only felid found primarily in true deserts. It prefers areas of sparse vegetation mixed with sandy and rocky areas, which support rodent and small birds, the predominant prey. In Algeria, sand cats have been reported from areas bordering great dune expansions, large sandy wadis and in areas with alternating rocky and wide sandy valleys. In Morocco, evidence of sand cat was found in sandy areas with the perennial gras Panicum turgidum, low bushes, and Acacia Acacia tortillis ssp. The sand cat has been recorded up to 2,000 m. In Turkmenistan, the sand cat seems most abundant amongst extensive stabilized sand dunes and heavier clay soil habitats. In the northern areas between the Aral and Caspian seas, it occurs only sparsely in the more claylike desert soils of the Ustyurt and Mangyshlak regions. On the Arabian Peninsula, sand cats have been recorded in sandy habitats but also gravel/rocky and even volcanic lava fields e.g. Harrat in Jordan and Saudi Arabia. In the United Arab Emirates, the sand cat was found in inter-dune gravel flats with scattered calcrete hills bordered by sparsely vegetated sand dunes and in sand dunes areas. In the Uruq Bani Ma'arid Protected Area, Empty Quarter, Saudi Arabia, the sand cat showed a small preference for the dune system in comparison to the gravel valley habitats and escarpment plateau. A habitat suitability study in central Iran indicated that sand cats preferred sand dunes covered with Haloxylon persicum. In Iran, it is also often found in flat plains and sand dune landscape dominated by saxaul species. Availability of food and cover seems to influence the habitat use pattern of the sand cat and its habitat selection. In the central landscape of Iran, sand cats depend on shrubland offering good cover, stabilizing soil for dens and harbouring a higher density of rodents. In addition, agricultural patches seem to create an important food patches for the sand cat prey. In Syria sightings are mainly from sandy habitats dominated by dwarf perennial shrubs Calligonum comosum and Stipagrostis plumosa. In north-east Jordan, they were reported to prefer sandy desert and depressions without Acacia.

Ecology and Behaviour

Many aspects of the behaviour and ecology of the sand cat are still poorly known. The sand cat is a solitary species. Males and females only come together for mating. The sand cat is mainly nocturnal and strictly hunts in the night. However, some diurnal activity in Arabia has been recorded, especially in winter when conditions were cooler. The sand cat rests in burrows during the day in summer to seek protection from high or low air temperatures and to minimize the loss of moisture. Burrows are usually found at the base of bushes but also in open areas or beneath rocks. Such dens can have multiple entrances and may be used by different individuals at different times. Sand cats are good diggers and can create their own burrows. However, it also inhabits abandoned burrows of desert foxes (Vulpes rueppellii, Vulpes zerda) or those of rodents and desert hedgehogs which are then enlarged. In the Moroccan Sahara, sand cats seem not to use burrows but instead hide between rocks or vegetation during the day in winter. The sand cat is not a good climber or jumper. However, in Morocco, they were observed to rest in bird nests in acacia trees Acacia raddiana.

With its exceptionally keen sense of hearing, it can detect prey under the sand and dig it rapidly out. The sand cat is capable of satisfying its moisture requirements from its prey, allowing it to live far from water sources. When the sand cat leaves the den at night it usually first observes its surroundings before moving away. This behaviour is repeated when it returns to the burrow. If threatened, the sand cat crouches beside rocks or tussocks, or even on bare ground, remaining immobile and is therefore very difficult to see. It also has the tendency to close its eyes against spotlights at night.

The home ranges of sand cats are quite large. A study done in Israel indicated that males maintain overlapping territories of about 16 km² and travelled an average nightly distance of 5.4 km. In Saudi Arabia, in the Saya/Umm Ar-Rimth reserve, annual home ranges of 19.6–50.7 km² were estimated. In Morocco, home ranges were estimated at 275 km² for 3 females and 319 km² for 7 males. There seems to be considerable overlap between seasonal ranges of males and females. Urine marking and vocalizations are used by both sexes to maintain social organisation. Sand cats are preyed on by snakes, large owls, jackals, foxes and wolves.

Births have been reported from January-April in the Sahara. Births have been reported in April in Turkmenistan and around September-October in Pakistan. In the Uruq Bani Ma’arid Protected area, Empty Quarter, Saudi Arabia, sand cat kittens were recorded between May and August. In captivity, births did not occur seasonally. Oestrus lasts 3 days, the oestrus cycle for 11–12 days and the gestation period for 59–67 days. Sexual maturity is attained at 9 to 14 months. Although the average is 3 kittens, litter size varies from 2–8. Age at independence is not known but young sand cats grow rapidly, and it is assumed that they become independent relatively early at around 6–8 months.

Threats

The major threat to the sand cat is habitat loss and degradation which may lead to population fragmentation. Arid ecosystems are in some regions rapidly degraded due to road and settlements expansion, recreational human activities such as off-road driving, land conversion for agricultural purposes and through overgrazing by livestock, especially by camels and goats, which also can reduce the prey base. Habitat is also destroyed through political strife and civil war.

The micro-distribution of the small mammals which make up an important part of the sand cat’s diet is often found close to vegetation and does not extend into bare sand ranges. This has the potential to limit the distribution and density of sand cats in areas devoid of vegetation or during drought years that lead to a loss of vegetation. Sand cat populations may fluctuate, decreasing and increasing in response to environmental changes that affect prey availability.

An additional threat is the introduction of feral and domestic cats. They directly compete with the sand cat for prey and may also transmit diseases. Congenital toxoplasmosis was found to be a cause of mortality in captive animals in two Middle Eastern breeding centres. Another problem is domestic hunting and herding dogs, which can be abundant. Sand cats are also killed by people. They are often caught in traps set for other carnivores or poisoned or occasionally shot in southeast Arabia. Sand cats also sometimes get accidentally trapped in fences where they die if not released promptly. Locally, the species may also be threatened by the pet trade.

Another problem is human disturbance to which sand cats seem to be very sensitive. A constraint for its conservation is for a lack of awareness of the species and a paucity of knowledge about its status and biology which can hinder effective conservation measures.

Conservation Effort and Protection Status

The Sand cat is included in Appendix II of CITES. Hunting of sand cats is prohibited in Algeria, Iran, Israel, Kazakhstan, Mauritania, Niger, Pakistan, Tunisia and United Arab Emirates. No legal protection is in place in Egypt, Mali and Morocco.

In some areas the sand cat is treated with respect by nomads due to its role in religious stories and is not persecuted.

There is an urgent need for further investigation of the sand cat’s ecology, population size and trends, status, threats and distribution to enable the implementation of effective conservation measurements.

M. Pittet

Prey

The sand cat feeds mainly on small sand dwelling rodents such as spiny mice (Acomys spp.), jirds (Meriones spp.) gerbils (Gerbillus spp.), jerboas (Jaculus spp. and Allactaga tetradactyla) and hamsters but also may take sand grouse (Pterocles sp.), larks (e.g. Ammomanes deserti, Alaemon alaudipes) and partridges. It also takes the young of Cape hares (Lepus capensis) and preys on different reptiles such as desert monitor (Varanus griseus), fringe-toed lizards (Acanthodactylus spp.), sandfish (Scincus scincus), short-fingered Gecko (Stenodactylus spp.), spiny tailed lizard (Uromastyx aegyptia), horned and sand vipers (Cerastes sp.). Sand cats also prey on insects and may take locusts when they swarm. In Arabia, the sand skink (Scincus scinicus) and Arabian toad-headed lizards (Phrynocephalus arabicus) are thought to be important prey species.

Nomads know them as snake hunters – preying mostly on two viper species by hitting them hard on the head and then biting on the back of the neck for the kill. When there is surplus meat from larger prey, the sand cat caches it under an insulating layer of sand for later consumption.